Jason Isaacs has played a wide range of characters in his career, including Colonel William Tavington in The Patriot, the infamous Lucius Malfoy in the Harry Potter films, a grieving father in Mass and Captain Gabriel Lorca on the television series Star Trek: Discovery. Now, Isaacs plays the title role in Archie, a miniseries currently streaming on BritBox, an online video subscription service that focuses on British content.

Archie, a BritBox original, presents Isaacs as Archie Leach, who later became the iconic movie star known as Cary Grant. The project is executive produced by Grant’s only child, Jennifer Grant and her mother Dyan Cannon, the actor’s third wife who also authored the book Dear Cary: My Life with Cary Grant.

The four-part series delves into Grant’s tumultuous childhood in the UK, his transformation into a Hollywood legend and the conflicts between his dual identities, particularly during his years with Cannon. Jeff Pope, recognized for fact-based dramas like Stan & Ollie and Philomena, helms the series as writer and producer.

In an exclusive interview with Casting Networks, Isaacs shared insights into his choice to embody the role and the lengths he went to authentically portray the character. Isaacs also reflected on the link between unresolved childhood trauma, as depicted in Grant’s life and toxic behavior in adulthood.

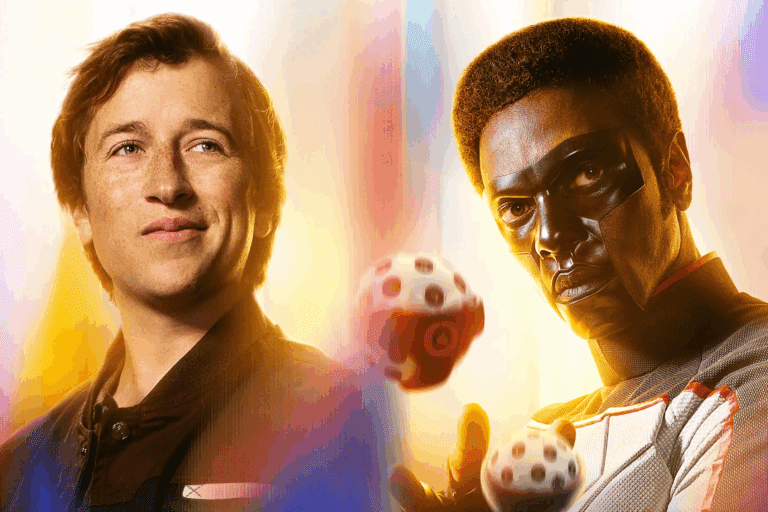

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios What intrigued you about taking on the role of Cary Grant, considering the risk of portraying such an iconic figure?

I was offered the job and immediately thought, ‘Absolutely not! Who would be moronic enough to try and play Cary Grant?’ Then I saw it was written by Jeff Pope. He is a man I’ve admired for a long time. He has a decades-long history of turning real-life stories into great drama in Britain. I wondered why he would have written a star treatment and be foolish enough to put Cary Grant on the screen.

As soon as I opened the first page, I realized there was a reason it was called Archie – Cary Grant was a fictional character that Archie Leach created to hide from the world how badly damaged and badly scarred he was and how entirely unlovable he felt. He created the polar opposite of who he was and what his life experience was. And it worked. He became the most lovable, desirable person in the world. But all that did was make those childhood wounds wider and more open and more painful.

That aspect drew you in after the initial reservation?

That felt like something that I did want to play. You’d be a moron to try and play Cary Grant or think that you could in any way recreate the charisma that he had on screen. But offscreen, when he got off set and shut his front door…he was a very, very different person.

How did you approach portraying a character who essentially created a persona to hide his true self? Did Grant’s film work offer any insight?

The films are useless because, in the films, he’s playing something he wished he was. I read all the biographies and I spoke at great length to Dyan and some length to Jennifer, then read other biographies where people told stories about him. I found unpublished things – an illicitly recorded tape of him.

[People are] completely wrong if they think he had that sense of certainty, masculinity and unflappability that he displayed on camera because he was in every way flappable. He was very thin-skinned. He was very emotional. Today, we’d label him with a bunch of acronyms: OCD, ADHD, PTSD, all of it.

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios In your research, how significant were the conversations with Dyan Cannon in understanding the complexities of Grant’s life?

I thought Dyan’s book was remarkable when I read it and she expanded much more when I spoke to her. Not only has she taken her pain and the mental torture she suffered in his hands, but she wrote about it long enough after the fact that she could be generous in retrospect and see the fault lines in his behavior… and that there was nothing she could have done. He was his own worst enemy.

Listening to her, how did those stories make you feel about the man you were preparing to portray?

I felt anger on her behalf as a father of young women, what she went through. But she also loved him and she saw into his heart. What she saw, when she shared with me, was that he couldn’t control [his behavior] and was broken by it.

There’s a reason he took LSD hundreds of times with a therapist to try and quiet the torment in his soul that stretched back to his childhood but also came from the dissonance, the gap between what the world loved him for and what he felt like inside.

With all the information you gathered, how did you merge these insights to embody the essence of Grant?

There’s the outside and the inside [of Grant]. I’m never going to be the guy who walked into any room and stopped it dead. Nonetheless, with the help of an extraordinary makeup and hair department and these brilliant Savile Row bespoke tailored suits [I could convey] something of the way he looked on the outside, but the inside was really hard.

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios In what way?

You want to help the audience get past the fact that on the outside, I don’t look like him or move like him. I had to try to meet [the audience] halfway. I had to work out what it was like to feel like him. I was desperate for a recording somewhere – a sight of him having a chat or talking to someone – because the stuff on film is nothing like him. A couple of times he made a speech in public, but he didn’t do recorded interviews. He didn’t want the public to see the mask slip.

Luckily, you got access to a 1980s recording of an interview with Grant conducted by a student journalist under an agreement with the actor that it would not be recorded. Except it was. Tell me about that.

Through a bit of detective work, I tracked it down. [The person] hadn’t played it to anyone for 40 years out of respect for Cary Grant, whom he was a huge fan of. He very generously shared it with me on the understanding that I wouldn’t let anyone else hear it. Not because [Grant] says something particularly controversial, but because it was him unguarded.

Did it aid in shaping your understanding of him?

When I heard the man – even though it was the last year of his life – I heard those fault lines that Dyan documents so brilliantly. I heard insecurity, I heard belligerence, I heard fear of being misunderstood. I heard many, many colors that you don’t hear on screen. That was the last piece of the jigsaw.

I thought, “Okay, I’m ready, to jump in now.” It was still a very anxious day, that first day I went to set and had to speak. But I thought, “Okay, I’ve heard Archie. Everybody else has heard Cary, but I’ve heard Archie.”

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios Do you view his story as emblematic of classic Hollywood stars who reinvented themselves despite inner turmoil? Marilyn Monroe feels like an example of that.

I don’t, because I know so many people who are not in the entertainment industry whose lives are damaged by the scars from their childhood that they’ve never managed to heal. You don’t have to be in Hollywood. The fact is, there are some broken people in Hollywood. But broken people are working in my local supermarket. Their relationships and their serenity are destroyed if they don’t manage to find ways to heal those scars from the past and break the chains for the future. Some [broken] people are writ large and they’re the size of billboards and known the world over. But I don’t think it gathers any more people than I find in my local park walking their dogs.

However, the broken ones at the very top, like Cary Grant, didn’t just get there by accident.

I don’t think you get to be that big a star unless you really want it and need it. And you need it because something is really cracked in the mold.

Now, many people want it, need it and don’t get it. But the ones who get there that I’ve met, who are absolutely at the top of the tree, that’s not what drove them there. That’s not what created a volcanically burning need inside them that blazed through all their competitors and got them there. There was a nuclear toxicity that made them seek what they thought was something that would heal them and of course, it always did the opposite.

I don’t have any friends in the acting business who, at least when they started, were completely balanced and serene. You wouldn’t do this job unless you were seeking some answers to things that had disturbed you in life.

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios

Photo Credit: Matt Squire / ITV Studios Are those answers found in playing characters adored by others?

No. If you’re looking for answers, if you’re looking to fill that hole inside yourself with other people’s love, you’re really fucked. But I have found and understood an awful lot about who and how I am and how I can be better by walking in other people’s shoes. Definitely.

Casting directors use Casting Networks every day to discover people like you. Sign up or log in today to get one step closer to your next role.

You may also like: